Alexander Hurezeanu is a PhD Candidate at Toronto Metropolitan University in the Communication and Culture Graduate Program and teaches in the Centre for Preparatory and Liberal Studies at Toronto’s George Brown College. His research examines how gameplay experiences produce new opportunities for transcultural communication in Eastern and Western cultural contexts.![]()

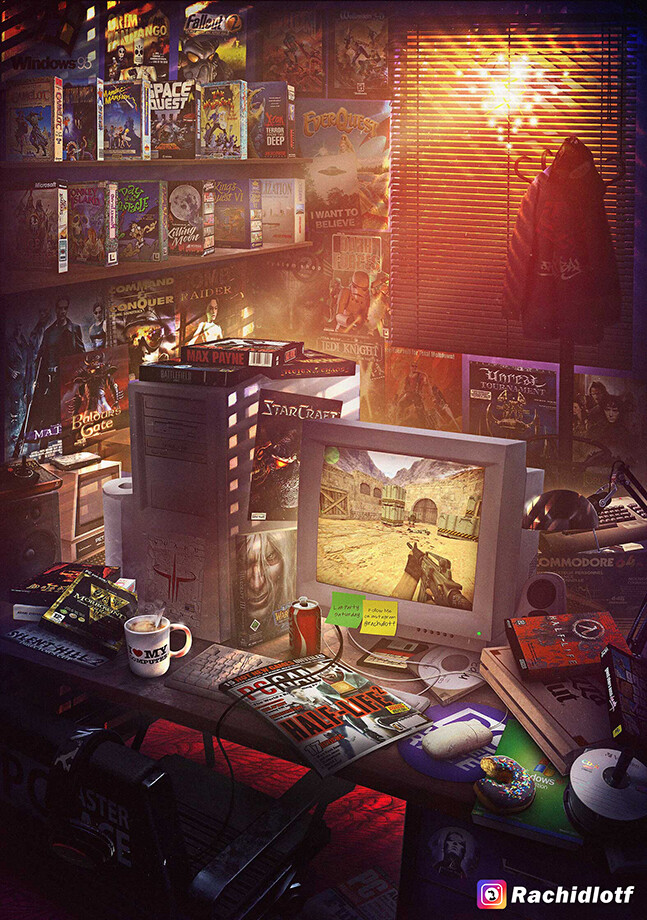

Nostalgic reimagining of early 2000s PC gaming at its finest. Art by Rachid Lotf: https://www.artstation.com/artwork/2xk02a

Nostalgia is an infamously contentious concept in game studies and gaming culture. The popular discourse surrounding nostalgia’s influence over video game production and consumption is often highly critical, as nostalgia is frequently judged to be a driving force behind creative stagnation in the game industry. In an article published in The Atlantic in 2015, Mark Hill makes the prescient claim that “the medium of video games in particular makes it easier to profit from players’ nostalgia—and it’s threatening to take a major toll on the gaming industry’s creativity and financial stability.” As such, older gamers have “more responsibilities and less time to form emotional connections with new games” (Hill), which is why, for many large companies, the safest return on investment is to simply remake, remaster, and renew sequels to legacy franchises. With the average gamer today being 32 years old (“2023 Essential Facts”), it is easy to agree with Hill’s assessment of nostalgia as a stagnant yet highly profitable mode of cultural production in light of the immense successes of games like Capcom’s recent Resident Evil 2, 3, and 4 remakes, Blizzard’s Diablo 4, or Square Enix’s Final Fantasy VII Remake series. That said, it is equally important to acknowledge nostalgia as a nuanced and multifaceted affectual concept that possesses potential as a driving force for unique and novel forms of worldbuilding and storytelling. In what ways, then, does nostalgic gaming or nostalgic reengagement with virtual worlds provide space for new and emergent experiences?

To answer this question, let us explore the role that nostalgia plays in forming and maintaining the active community behind Project 1999: a free-to-play “classic” EverQuest server that operates under legal permission. Released in October of 2009, Project 1999’s stated goals are to “restore the magic and difficulty of the original EverQuest game, including the mechanics, interface, and challenges of Original Content, [and its expansions] Kunark, and Velious.” Viewed through the framework of Hartmann and Brunk’s concept of “progressive nostalgia” (675), Project 1999 demonstrates significant elements of reflexive engagement with nostalgia that is firmly situated in the past while simultaneously generating space for creative, subversive, and non-commodified forms of social play and storytelling. As a fan server that still continues to attract new players, Project 1999 provides an enduring game world that is rooted in the nostalgic-laden principles of EverQuest’s classic design while seeking to provide players with unique play experiences. Through an autoethnographic account of my own experiences playing EverQuest as a youngster and my reengagement with the game through Project 1999 as an adult, this essay explores the concepts of progressive nostalgia and nostalgic re-enactment as useful approaches for understanding the appeal of older online games. I argue that fan servers, like Project 1999, purposefully reject many modern gaming conventions in order to reconstruct past gameplay experiences in the present as a method for providing uniquely progressive and meaningful play experiences.

Nostalgic Play

It is important to delineate what we’re talking about when dealing with nostalgia in the context of video games. That tinge of bittersweet longing that affects some of us whenever we hear the Super Mario Bros Level 1 theme is tied to the “psychological weight of how nostalgia relates to our identity and maintains congruity between our current and past concepts of ourselves” (Madigan). This is especially true when we view video games as experiences that centre us, the players, as the main actors. Gaming psychologist Jamie Madigan claims that “video games have the potential to elicit more nostalgia than any other medium.” This is because certain games that appealed to us in our formative years “create continuity between our current and ideal selves by remembering the special landmarks in the history of gaming that we were part of. Maybe you were hardcore into Ultima Online or EverQuest and thus can see yourself as part of the birth of massively multiplayer games” (Madigan).

By examining some of the more constructive and inspiring aspects of nostalgic engagement, we may articulate a progressive theoretical framework. In their article titled “Nostalgia Marketing and (Re-)Enchantment,” business and marketing scholars Benjamin J. Hartmann and Katja H. Brunk identify the concept of “enchantment” as a central theme to how individuals experience and internalize brand loyalty and product consumption:

A dominant focus on rationality in many parts of everyday life displaces and reduces the room for imagination, fantasizing, wonder, romance, and magic over time. However, because such moments of specialness—or enchantment—are an important and cherished part of human existence, this quest for enchantment leads to a growing desire for consumption that promises to recuperate these lost aspects. (670)

To that end, it becomes the job of the media/production company to reproduce enchantment through the constructed “romance of the return to producing and consuming somewhat archaic and less rationalized community-supported [products]” (Hartmann and Brunk 671). While this approach to understanding nostalgic production and consumption certainly affirms Hill’s pessimistic argument of nostalgia-driven product sovereignty, Hartmann and Brunk interestingly lay out several routes to nostalgic enchantment. As such, I’d like to specifically focus on their concept of “progressive nostalgia” as a mode through which consumers engage in “productive, reflective, and anchoring [dimensions] of nostalgia that bring past and present into dialogue” (Hartmann and Brunk 675). Progressive nostalgia is illustrative of a consumer’s desire to return to a selectively moral past that can affect and shape their current situation: “In this case, consumers valorize past-themed brands as tokens of a cultural condition that now appears to be superior in some way. This condition and its tokens can now be used to shape a better present and future” (Hartmann and Brunk 677). Hartmann and Brunk term the consumptive engagement of progressive nostalgia “re-enactment” as the consumer’s goal is to re-enact “morally valuable aspects of a lost time and place in everyday life” (677). Progressive nostalgia is a reflexive mode of engagement that embraces contemporary culture by prioritizing an individual’s lived experiences.

In this way, the past and the present are brought into dialogue as progressive nostalgia gestures towards “utopian visions of a better society than [our] current one” (Hartmann and Brunk 677). How then, can we utilize progressive nostalgia for the re-enactment of past gaming experiences? And how might these past experiences provide space for meaningful re-enchantment with virtual worlds? Hartmann and Brunk suggest that re-enactment through progressive nostalgia creates opportunities for re-enchantment that entail “the symbolic use and redemption of former practices and brands… thereby establishing a renewed sense of belonging in a [contemporary] consumer culture that [some may] find partially alienating” (679). While Hartmann and Brunk do not cite games in their discussion of progressive nostalgia, it is easy to identify the concept by contrasting the practices of non-profit classic fan servers, like EverQuest’s Project 1999, to the game’s modern, official servers that operate in parallel. From here, we may begin to extrapolate how approaches to older online games through progressive nostalgia are capable of providing novel and meaningful gaming experiences in the present day.

Hartmann and Brunk’s overview of the different (re-)enchantment routes and their underlying nostalgia modes

EverQuest in 1999

It is thus necessary for me to discuss my own experience with EverQuest. In this manner, I hope to provide an autoethnographical account of my experiences as illustrative of Hartmann and Brunk’s concepts of re-enactment and progressive nostalgia. Released in March of 1999, EverQuest is one of the most successful MMORPGs ever, being one of the first truly successful 3D MMOs while also formalizing the format and conventions of the MMO genre. Indeed, T.L. Taylor, in her formative and highly influential ethnographic work on online communities, wrote about EverQuest’s most significant and consequential feature being “the notion of shared persistent world environments full of both instrumental and free action” (28). In my case, as a young person seeing the 2-page ad spreads in my issues of PC Gamer magazine, EverQuest was a game that captured my imagination with the seemingly limitless possibilities of playing in a completely immersive, online environment with people from all over the world. Having convinced my mother that my younger brother and I would help to pay for the monthly subscription fee if she agreed to cover the first 3 months, we booted up EverQuest on our Windows 98 PC and created our first avatar: a Drizzt Do’Urden-esque dark elf shadow knight. Ultimately, though, our experiences in the world of Norrath lasted less than a year, and by the time the first expansion, The Ruins of Kunark, was released in April 2000, my brother and I had firmly given up on the supposed magic of EverQuest.

Early EverQuest ad featured in PC Gamer magazine. Archived by the website Video Game Print Ads: https://vgprintads.tumblr.com/post/182544449275/everquest-pc-usa-magazine-spread-1999

As an adult, I never maintained much of a nostalgic longing for EverQuest. This is largely due to the fact that my play experiences as a youngster were thoroughly tarnished by my general inexperience, inability, and unwillingness to adapt to the new and still forming genre conventions that differentiated EverQuest from the single-player RPGs that I grew up playing. Accentuated by the fact that it was impossible for me to convince any of my friends to play the game with me, as many of them scoffed at the idea of having to purchase the game at full price and then pay a monthly subscription fee just to play it, EverQuest was a gaming expedition that was doomed to fail. Perhaps it was due to my youth, naiveté, and social inexperience in communicating with complete strangers over the internet that EverQuest proved to be a fruitless and impossibly challenging experience. And so, my younger brother and I, taking turns on a seemingly endless cycle of defeats and losses, gave up, and never thought to return to Norrath ever again.

Project 1999

That changed in 2019, when a fantasy author that I follow by the name of Michael J. Sullivan posted on his blog that he and his partner had just begun playing EverQuest again after a nearly twenty year hiatus. But what had managed to attract Sullivan back into Norrath? After all, EverQuest still persists to this day as a mostly free-to-play MMO on its official servers. But for Sullivan and his partner, the modern EverQuest experience is highly illustrative of Hartmann and Brunk’s sense of alienation evoked by contemporary consumer culture, as “today’s EverQuest bears little resemblance to the original experience.” Indeed, perusing EverQuest’s official website reveals various microtransactions and purchase packs that are common in today’s MMOs. As expected, EverQuest has adopted many of the contemporary trends in gaming that allow players distinct advantages through sheer purchasing power. In contrast, Sullivan explains that a group of fans have been operating and maintaining a completely free-to-play server called Project 1999, or P99, and had just opened a new sub-server called Green, which Sullivan claims is “the most accurate re-envisioning of the original game.” As a fan server that maintains a relatively small but loyally consistent userbase, the nostalgia that many have for classic EverQuest is most certainly what has kept this particular small subsection of internet gaming alive and well for over 14 years. But what defines the so-called classic EverQuest experience? Sullivan summarizes it as often harsh and occasionally baffling, as it lacks many of the “modern conveniences” of contemporary MMOs. While Sullivan criticizes the occasional slowness and tediousness of the overall experience, he also voices his deep appreciation for the way the game forces players to band together in order to overcome the overwhelming odds stacked against them, thus echoing Hartmann and Brunk’s recognition of how progressive nostalgia may redeem former symbols and practices (679). In short, it is the most fun that Sullivan has ever had in a computer game, and with that, he drops the names of his character and his partner’s character and beckons readers to join them.

P99 serves as an extremely laudable example of Hartman and Brunk’s concept of nostalgic re-enactment, especially in the manner through which EverQuest fans banded together to meticulously recreate as much of the “original” experience of playing EverQuest in 1999 as it felt to them. Alternatively, the Daybreak Game Company, EverQuest’s official owners, provides classic “progression servers” for nostalgia-laden players to join. That said, many of the official servers’ modern monetization practices remain, thus evoking a type of superficial nostalgia that Hartmann and Brunk call “re-appropriation” through which “consumers valorize past-themed offerings purely as ironic, hipsterian, and quirky fashion items that can enliven the present” (675). But for those players discovering EverQuest for the first time and actively choosing to play on P99’s servers, a much more interesting concept raises its head: Why play P99 over other more modern, more official, and more accessible MMOs? YouTuber Ion Blaze answers this question by pointing to classic EverQuest’s class offerings, its uniquely unrelenting difficulty, and its required modes of social interaction (01:28–17:30). But what specifically resonated with me is what Ion Blaze points out in one of his later videos, which is the fact that “Some of us were too young to appreciate the game… Many people come back to servers like P99 to experience content that they never even had the chance to experience back in the day” (04:02–05:12). And so, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, I opted to reinstall EverQuest and urged my brother to do the same. We re-embarked upon our journey through Norrath that we had abandoned over twenty years ago, and, echoing Sullivan’s sentiments, it was some of the most fun we had playing a video game together in many years.

It took time for my brother and I to readjust to what was once considered cutting edge in 1999: The clunky and unintuitive UI, the awkward movement and camera options, and the complete lack of world and city maps, but as we grouped with other players, we had the chance to re-experience what we had been too young to understand or appreciate decades ago. In many ways, the experience of playing EverQuest on P99 was somehow novel, exciting, and affirming, as there were no pressures to join guilds in order to engage in raids, no paywalls to cross in order to access locked content, and no nefarious microtransactions that encouraged in-game meritocracies based on wealth. A nostalgia began to form in me for a past that I had never experienced, in which MMO gaming experiences were defined by their longevity through the sheer enchantment of engaging with the world and through truly meaningful social interactions. Interestingly, Hartmann and Brunk identify this unique sense of nostalgic disorientation as “the specific sense of dislocation that underlies progressive nostalgia” (677). In short, progressive nostalgia doesn’t seek to reductively anchor one’s experiences solely to their past thoughts and feelings, but instead seeks to recognize how past experiences may be re-enacted in order to identify and critique contemporary issues while providing new and meaningful experiences. Regardless of how I may have felt when I was younger, the re-enactment of old-school EverQuest in P99 helped me to appreciate “the valorization of such past practices as a general benefit for society, a moral high ground that creates welfare not only on an individual level but also on a cultural level” (Hartmann and Brunk 678). Project 1999 was a game entirely held up by its community, for its community, without any brazen monetization practices, and kept afloat through the sheer passionate nostalgia of its fans, players, and community volunteers. Over twenty years later, I have finally managed to simulate living in the world of Norrath in a way that has exceeded my childhood experiences and expectations while fundamentally changing the way I see online role-playing games. EverQuest still has many stories to tell, and fan servers like Project 1999 openly welcome new players while still beckoning older players back into the fold through their promises of nostalgic re-enchantment.

Works Cited

“2023 Essential Facts About the U.S. Video Game Industry.” Entertainment Software

Association, 26 June 2023.

Hartmann, Benjamin J, and Katja H. Brunk. “Nostalgia Marketing and (Re-)Enchantment.”

International Journal of Research in Marketing, vol. 36, no. 4, 2019, pp. 669–686.

Hill, Mark. “How Nostalgia Is Ruining Video Games.” The Atlantic, 22 Nov. 2015.

Ion Blaze. “Who Still Plays EverQuest in 2022? (Video).” YouTube, 02 Dec. 2021.

—. “Why You Should Play EverQuest in 2022 (Video).” YouTube, 16 Nov. 2021.

Madigan, Jamie. “The Psychology of Video Game Nostalgia.” The Psychology of Video Games, 6

Nov. 2013.

Project 1999. Accessed 1 February 2021.

Sullivan, Michael J. “P1999.” Author Michael J. Sullivan’s Official Website, 11 Oct. 2019.

Taylor, T. L. Play Between Worlds: Exploring Online Game Culture. The MIT Press, 2009.